“For all of us there is a twilight zone between history and memory; between the past as a generalized record which is open to relatively dispassionate inspection and the past as a remembered part of, or background to, one’s own life.” Eric Hobsbawm

It is June 5, 2018 and I am preparing for a one-month research trip to Mozambique. While I have planned this trip as part of my dissertation on the Cold War relationships between Mozambique and the GDR, I chose to take along my father, who had worked in Beira, the fourth largest city in the northeast of the country, during the 1980s on the construction of the railroad line Beira-Dondo. As part of his contract, he brought his wife and his two daughters along. Our family stayed in Mozambique for two years before returning to the GDR in 1984. What would he recall after all those years? Would he be able to remember the places he worked? Would those places still look the same, will they have vanished, or changed completely? And what would I remember, as I was only three years old when we left for Mozambique. Although he had shown us slide after slide in the 1990s, those images and stories had faded over time. Would I remember anything? I decided to bring some of these photographs with me in the hopes of locating some of the places from my childhood.

Arrival

In the early morning, we arrive in Maputo. As the capital of Mozambique, it is our first stop. All East Germans arrived in Maputo first, stayed there for a couple days before departing to their final destinations. Although it is winter season, the air is hot and humid. I catch myself thinking, “thank goodness I did not choose to do field research here in the summer”. We settle into the apartment, and then take a walk through an upper-class neighborhood. We travel through the fenced and highly-secured embassies, passing women selling fruit and vegetables on the street. I can feel my father’s happiness returning after all those years, as well as his eagerness to explore the city. His excitement is contagious; I cannot wait to explore the country with him and rediscover all the places from the photos.

Looking for Rubi

One of the most intriguing photographs I bring with me is of a building with a sign that reads RUBI. Once the tallest building in Maputo, it is located on a corner along the Avenida Samora Machel. Illuminated, the big four red letters resemble an advertisement. Beyond receiving the photo from my father’s collection, I am unfamiliar with its details. Similarly, all my father remembers is that it was taken in Maputo. I know tracing down images without any details would be a difficult task, but I am nonetheless hopeful. One day, after finishing some research in the Arquivo Histórico de Moçambique, we see a small park with a craft venue in the middle. Suddenly, I freeze, trying to contain my excitement. There it is: my RUBI building. Its colors had faded but the structure of the building is still intact. RUBI’s discovery motivates me to look for more places, buildings and signs corresponding to my photos. Over the next two weeks, as we travel to Beira, Dondo, Mafambisse, Messica, Chimoio, Manica and Machipanda, I take my own photos of places, buildings and signs I discover. In doing so, I myself restage moments of family-time my father captured and change narratives.

Dom Carlos Hotel

Our second stop is Beira, the city we called home for two years. The airport is small. In comparison with Maputo, everything seems more provincial. As soon as we sit in the car that brings us from the airport into the city, memories begin to resurface for my father. We drive along a bumpy-sandy road, passing people on bikes and a modern Chinese hotel complex. My father is shocked at how much has changed and repeatedly comments that the city “did not look so run down in the 1980’s”. We pass the Dom Carlos Hotel where new incoming East German families had stayed until they were able to move into their assigned houses and apartments. The next day, we visit the Dom Carlos while taking the “Macuti neighborhood” tour. One of the pictures I have with me is of a hotel and was taken by one of my father’s colleagues. It depicts the modern architectural building sometime in the early 1980’s, painted blue, and surrounded by trees. Once a hotel on the rise in Beira and a destination for many foreign aid workers, today it stands abandoned and in an unsettled owner-and-property situation. Even the attempt to put some fresh paint on the walls does not prevent the hotel from looking like ruins. The roof and windows are absent, and the outside walls are plastered with cell phone advertisements.

My Memories

When it comes to abandoned places, I am the first one who wants to take a closer look and explore the inside. I am curious to see if I would remember anything there. I step inside, and immediately I am drawn to a painting on the wall, amazed to see that it is still in full display, completely untouched. I would imagine that in Germany this type of abandoned building would have already turned into a graffiti project. As I take a picture of the painting, I remember that I had gone through some photos earlier showing East German families celebrating Christmas at the Dom Carlos Hotel. Later on, back in our hotel, I go through my digital collection and locate the image I thought I remembered seeing. It is a photograph my father had taken during a Christmas get-together at the hotel. East German families and their children sit in the lobby, gathered around a table with an illuminated, plastic Christmas tree. Someone is playing the accordion while others unpack their presents and take pictures. Looking at both images, one can decipher the beauty and destruction of the hotel over the passage of time. It is both fascinating and odd that the only piece that survived it all, is this painting; it is as if it holds on to the memories of that time—those now forgotten and buried in rubble.

My Mother

Over the next days, I still wonder if my memory of Beira was constructed through the photographs from the 1980’s. I receive an answer to this question once we visit our old home. Driving along a road at the shore, I am surprised to see that our former house is closer to the beach than I expected. I had also pictured the neighborhood differently with only one side of the street spotted with houses. The other side—I imagined—must have been just bushland with banana plantations. Right there, I realize that my memories are misled and made up from the stories my mother had told me. The entire street consists of terraced houses which have been there since the Portuguese occupation. Respectfully approaching the current tenants, we explain to them that we lived “here in this house”. I ask for permission to take a picture of me standing on their balcony, the very same way my mother once stood there being photographed by my father. The shade-giving papaya tree at the house’s front was taken down and replaced by a small palm tree. The house still looks the same despite its barred windows having undergone some color changes. Now, the garage is closed off and the small gate replaced by a larger one. The house continues to host families who work for the Caminhos de Ferro de Moçambique (CFM), the railroad company my father worked for.

My Father’s Happy Place

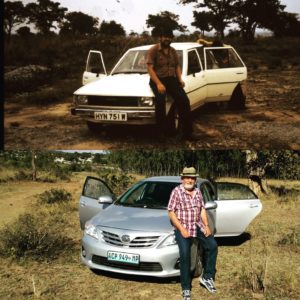

We then go further into the country to stop at different project sites my father worked at. My father worked for the CFM in Beira and occasionally traveled throughout the country for work assignments. With difficult road conditions en route to projects and security measures at the project sites, these assignments sometimes took days and weeks to complete. For this, he had to leave the family behind. Therefore, we only heard the stories about these places and later saw photos he took. I realize the importance of documenting his return journey once I see his reaction to these places. I begin to restage the photos of him in the same locations today. This means placing him into pictures—a reversal, as he had photographed his daily work and family life behind the camera. I choose two older pictures I have of him and restage them.

The first one is a reenactment of a 1983 photograph at Ifloma—a wood factory one-hundred-fifty miles from Beira—in Messica. My father had worked here for several months, though he cannot remember the details of when the picture was taken. He surmises: maybe a quick stop after a long workday on their way back to Beira or the project housing they stayed in. The image seems a little bit off since the other person in the photo either did not want to be photographed or did not realize that a photo was being taken. He is bending down, distracted by something. To reenact the picture is easy since only the car and the shoes seem to be different. Later, when I compare the two pictures, I realize that my father has always worn checkered shirts.

My Father’s Defeat

The second photograph I take of my father is connected to a longer story at one of his work sites. In Beira, my father and I have permission to join construction workers from the CFM in Dondo on their repair and maintenance machine to the Pungue Bridge. One of the best visually documented projects, I heard stories of its construction, bombing, provision and final repair. It feels natural to go and see the bridge today. When we hear that the organized trip with the CFM fell through, we try to get to the bridge ourselves on a dam through the sugar cane fields in Mafambisse. Unfortunately, a regular car is only able to get you so far. So, the picture I take in comparison with the one from the 1980s portrays both, pride and defeat. Pride—after finishing the project of reconstructing the bridge, and defeat—as we are not able to get to the bridge on our own. I again realized how important it was for my father to revisit these places when I talked to him on the phone the other day. I asked him how, after a month of being back in Germany, he reflects on it. His first sentence is: “We could have made it!” It had really bothered him to not be able to visit the Pungue Bridge again.

Conclusion

The importance and impact of this trip differed for me and my father. I desired to see places my father had worked at and revisit the city we lived in. In sum, I was searching to validate my memories. What made the trip so special was that I was able to do this with a close relative – my father – who had lived and worked there. I was able to see the places in photographs and listen to the narratives from the photos he had shown me; they had fascinated me ever since. Furthermore, I also learned new things about my father. Not only that he’s been wearing plaid shirts since at least the 1980s, but also his gratitude of being able to visit Mozambique one more time. He never talked about going back, but I know now that it had been on his mind for an entire year since he left.

For me, the trip resurrected memories that I heard from my parents but was only now able to place into a geographical and social context. It is a family history that creates its own narrative separate from that of the collective. It is an individual approach of retracing (East German) history. Using private photographs as a visual narration aid is not just a tool for documenting personal lives; it is a powerful agent of historical change and challenges prevailing narratives that go beyond times and spaces, bridging past and present as a continuing story.

I would like to thank Feling Capela who inspired me to write this story down.