From NVA-inspired fashion, GDR-themed hotels and restaurants, GDR-product fairs and mail-order companies, to relaunched and newly created GDR brands like Halko’s DDR Schulküchentomatensoße: why do so many consumers in East Germany, and other former socialist societies alike, insist on socialist products and brands today when they were considered inferior alternatives to their western counterparts back then? Reviving a brand with previously negative associations and unfavorable product attributes defies conventional marketing and business logic. Hence, the standard explanation offered by consumer sociologists and historians is that these thriving socialism markets stimulate political opposition, a yearning for the “better” socialist past. From this perspective, when consumers interact creatively and playfully with the socialist past and engage in highly emotional consumption to revitalize themselves through socialist products and brands, they actively critique, resist, and in the process, invariably destabilize the capitalist status quo.

Although this explanation is certainly valuable, it has little to say about why socialism today is predominantly transported as a market-based consumption experience. Moreover, what alternative modes for expressing the relationship between the socialist past and the capitalist present are muted over time and why? What kind of socialisms are transported in these commercial images and meanings and what is their impact on the conditions of capitalism? What are the underlying cultural and ideological dynamics of this marketization? Intrigued by this fascinating subject, we, Katja H. Brunk (Europa-Universität Viadrina, Frankfurt/Oder, Germany), Benjamin J. Hartmann (University of Gothenburg, Sweden) and Markus Giesler (York University, Toronto, Canada), examined the development of the German Ostalgie market over the past twenty-seven years. Based on an analysis of empirical data including advertising material, movies, books, media articles, and consumer narratives, we developed a multi-stage, multi-actor model of hegemonic memory making.

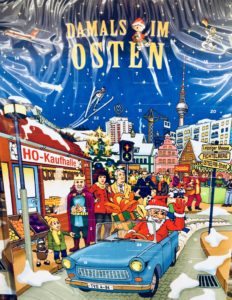

The Ostalgie market, one of the largest socialism markets in the world, emerged after the German reunification. When the Wall came down in 1989, consumers were finally able to buy long desired Western goods, which led to a period of hyper-consumption and the disappearance of socialist products and brands from the East German retail market. This phase of enchantment was short-lived, however. The shiny façade of Western consumer culture began to crumble when many East Germans were faced with harsh consequences of economic and political restructuring. This resulted in a hangover phase, characterized by the realization that capitalism was far from the land of milk and honey experience previously envisioned. It is during this time, the early 1990s, when the previously inferior and rejected East German consumer goods re-appeared, allegedly evoking feelings of nostalgia – a romanticized yearning for the “better” socialist past. Today, thirty years after the Wall was toppled, some products from the GDR era are still being relaunched (e.g., Undine cosmetics, Simson Schwalbe). Most consumer sociologists have taken this remarkable renaissance of East German products and brands as incontrovertible evidence for East Germans’ discontent and criticism of social and economic conditions in post-reunified Germany. Gathering the family around a simple socialist meal, rejecting West German food and lifestyle brands, or vacationing in a no-frills GDR-style retro hotel are seen as practices of resistance against West German preferences for efficiency, hyper-individualism, and status consumption.

However, we observed that the Ostalgie market’s romantic venerations of socialism changed considerably over time. They were crafted in West German marketing departments, advertising agencies and film studios who retailored political dissent into consumable emotional-nostalgic market resources in an attempt to restore political unity in four phases, each triggered by a historical disruption:

- Phase 1: the privatization of East German industry (1991-2000)

- Phase 2: the dismantling of German social security (1999-2005)

- Phase 3: the publication of Stasi informants (2003-2009)

- Phase 4: the Euro and global financial crisis (from 2008)

In each of these phases, a particular nostalgic image of the socialist past was crafted in response to East German political critiques of capitalism and was subsequently offered for mass-market consumption.

In phase 3 for example, the 2003 iconic Ostalgie movie Good Bye Lenin! transformed East German critiques of the hyper-individualism inherent in capitalist societies —which, according to an East German perspective, comes at the expense of the social and collective—into a banalized contrast between capitalism’s shallow consumer culture and socialism’s caring neighborhood idyll. Importantly, this highly therapeutic narrative did not naturally emerge from the memories of former GDR citizens. Rather, it was carefully crafted and popularized by a team of West German scriptwriters, producers, and promoters—at a time when West German politicians, journalists, and intellectuals, critically unpacking the activities of the famous “Stasi” (Ministry for State Security), condemned the GDR as a ruthless surveillance state of citizen spies, subsequently triggering a debate on the portrayal of the GDR as an “Unrechtsstaat”. This debate framed the socialist past purely in terms of mechanisms of repression and power structures and portrayed the GDR as a society of betrayal where nobody—not even family members—could be trusted. Commercial mythmakers (i.e. filmmakers, marketing agents, media professionals, brand managers) addressed this growing political tension and began refashioning the critical Stasi debate from the political level to that of consumption. They did so by cultivating consumable nostalgic memories that spotlight camaraderie and care, a re-imagination that was prominent in Good Bye Lenin! and thanks to which East Germany could then be channeled through consumption by revalorizing socialist brands like Spreewald pickles or the East German care package (the so-called “Ostpaket”) as tokens of a communal utopia, as nostalgia-framed identity salves that allow consumers to regain pride as former East German citizens.

Thus, the East German political resentment nurtured a hegemonic memory-making process that promoted a new consciousness of the bygone GDR as a morally superior alternative, a social paradise undergirded by social bonds and togetherness. These romanticized reconstructions paved the way for naturalizing the capitalist status quo by offering consumable identity salves that allowed East Germans to resolve identity stigma and express both their symbolic resistance to delegitimizing portrayals of an East German society of spies as well as their critique to capitalism’s individualism through consumption. Rather crucially this implies that marketing agents never just simply serve and respond to consumers’ nostalgic desires through emotional products and brands. Instead, they operate as powerful historians who frequently re-design how we can or cannot imagine the past, illustrating that history is malleable material.

With mythmaking of socialism being a multi-billion-dollar business, spanning industries such as entertainment, film, cultural heritage, advertising, consumer goods, food, product design, fashion, and the creation of extraordinary consumption experience, sociologists and historians need to adjust their theories on the political significance of socialism markets. The ability of socialist goods to help consumers challenge capitalism’s social and economic conditions must be questioned. While, on the surface, socialism markets may look like attractive avenues for consumers to take an active stance against status consumption, hyper-individualism and competition, they are ultimately strategies for capitalist societies to transform political dissent into highly emotional consumption adventures, thereby depoliticizing critique and nurturing consensus for the capitalist market system. Re-invoking innocent, emotional, and apolitical tales about the good life in socialism, these brands have a vital function for securing social order in turbulent times by giving citizens a sense of pride, control, and identity as consumers.

Sources:

- Brunk, Katja H., Giesler, Markus and Hartmann, Benjamin J. (2018), Creating a Consumable Past: How Memory Making Shapes Marketization, Journal of Consumer Research, 44(6), 1325-1342 https://academic.oup.com/jcr/article-abstract/44/6/1325/4159195?redirectedFrom=fulltext

- https://blog.oup.com/2018/07/beyond-nostalgia-understanding-socialism-markets/?utm

- Hartmann, Benjamin J. and Brunk, K. (forthcoming), Nostalgia Marketing and (Re-) enchantment, International Journal of Research in Marketing. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2019.05.002