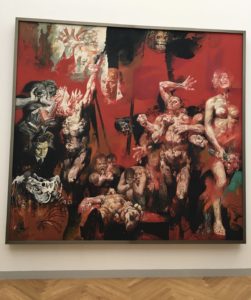

Roughly one year ago, on January 23, 2017, the latest addition to Potsdam’s museum scene opened its doors to the public: The Barberini Museum, an impeccable reconstruction of the 1770s baroque palace which was destroyed by an allied bombing attack in World War II. It is now one of Germany’s largest private art museums and home to the private art collection of the SAP[1] founder and former CEO Hasso Plattner. Yet what I am about to discuss here is not its baroque facade but what it has on display inside. After an opening exhibition on impressionist art in spring 2017, from October last year until this February, the museum presented its major collection of East German paintings and sculptures under the title Behind the Mask – Artists in the GDR. On display were works by more than 80 GDR artists, including many famous names such as Bernhard Heisig, Wolfgang Mattheuer, Gerhard Richter, Werner Tübke and punk legend Cornelia Schleime. The show was divided into categories such as Individuality and Historicity, Self-Portrait and Alter Ego, Art and the Collective, and Adaptation and (Trans)Formation.

The fact that the majority of exhibition space was dedicated to a permanent collection of East German art is remarkable for a German museum. More important, the exhibition represents an attempt – after major exhibitions in Berlin’s Neue Nationalgalerie (2003), the MdbK Leipzig (2009) and Weimar (2013) – to appreciate East German art for its artistic values. Through this approach, East German artists and their works, and in effect the GDR itself, become linked to various lines of art historical traditions and international movements. Simultaneously, the curators allow for the works to be interpreted in regard to the artists’ aim of creating a communist society, despite the often difficult political and ideological constraints of real existierender Sozialismus (“real existing socialism”).

The individual descriptions accompanying the art works are simplistic and one-dimensional interpretations, contradicting the efforts of releasing socialist art from its ideological cage. However, the works themselves are able to overcome such simplification. A particular success of the exhibition is the combination of individual and independent art works with two rooms dedicated to the sixteen huge paintings commissioned for Berlin’s former Palace of the Republic which housed the GDR parliament chambers, several cultural institutions, restaurants and bars. The building was demolished in the early 2000s and is currently being replaced by the Humboldt Forum, a modern museum in the shape of the former baroque Prussian city palace.

To be able to see these works in the spaces of an art museum provides a neutral context that is needed to observe them with “less prejudice,” something that so far happened mostly outside the German borders. This “paratext” of institutional appreciation creates an entirely different context for the psychological and physical visitor experience that many similar exhibitions often lack: the viewer is there not to see exhibits from the “other(ed)” Germany, but rather works of high artistic quality. The Barberini museum features large commissioned works that engage with utopian themes, moments of artistic crisis and local art school pride. It thus makes a major contribution to the appreciation of East German art on its own merits, rather than relegating it to the status of a historical remnant of regime that was colonized by overcome by Western culture, an idea that resonates with Thomas Oberender’s recent remarks.[2]

Indeed, when the Federal President, Frank-Walter Steinmeier, opened the exhibition, Plattner told a journalist that he thought East Germans and East German cultural contributions to 20th century culture had too long been neglected in unified Germany. Plattner emphasized that it was time for a re-presentation in an appropriate museum space in former East Germany. This view represents an appreciation of the unique East German cultural heritage that is long overdue and part of a wider trend. In her article in the German weekly DIE ZEIT, Anne Hähnig[3] argues that a paradigm shift is taking place particularly in the major East German museums when it comes to East German art, with large museums in Leipzig and Dresden heavily debating[4] or taking action to display East German art prominently as part of their permanent exhibitions.

Yet Barberini’s contribution to East German culture comes with a bitter aftertaste, for which one need only to look outside the museum’s large windows. Outside, the new and renovated buildings on the Alter Markt—also largely a product of Plattner’s generosity—are accompanied by the remains of a 1970s modernist university building which now faces demolition in order to be replaced by more neo-baroque facades. By destroying one of the few “historical” buildings in order to make the area look more coherently historic rather than keeping the tensions of Germany’s twisted 20th-century history represented within the urban, the contrasting approaches to Potsdam’s (built) cultural memory could not be made more apparent. Thus, Potsdam does its very best to erase all prominent traces of the GDR in its city center as if it really had only been, as Stefan Heym predicted, a footnote in world history and not living memory that still shapes the everyday of contemporary Germany. Through this, new tensions arise around how contemporary Germany wants to remember the GDR. The Barberini museum is only the beginning of another chapter in this debate.

[1] SAP is a European multinational software corporation

[2] http://www.zeit.de/2017/40/ddr-mauerfall-kinderbetreuung-west-ost-deutschland

[3] http://www.zeit.de/2017/43/ddr-kunst-museen-ostdeutschland-kuenstler-geschichte

[4] http://www.faz.net/aktuell/feuilleton/kunst/bilderstreit-im-albertinum-high-noon-in-dresden-15281890.html

Views and opinions expressed in blog posts and other publications on this website are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect positions of other members of the Third Generation Ost network.